An Interesting Spanish Tale of the Eleventh Century

Author: Unknown

Publisher: A. Neil

Publication Year: 1806

Language: English

Book Dimensions: 10cm x 18cm

Pages: 36

University of Virginia Library Catalog Entry, Sadleir Collection: PZ2.E575 v.4 no.5

A tale of religious and forbidden love, this 1806 chapbook draws heavily from Matthew Gregory Lewis’s The Monk, published in 1796.

Material History

The Mystery of the Black Convent is one chapbook in a larger compilation of chapbooks. The compilation is bound in calf leather with gilded printing on the spine, indicating a once-luxurious appearance. The volume measures 10cm by 18cm, a size that suggests it was intended for easy handling and portability. The front cover of the volume shows significant damage, revealing extensive use and possibly poor storage conditions over the years. This wear not only affects the book’s aesthetic appeal but also speaks to its resilience and the varied environments it has survived.

Inside, the compilation features a range of chapbooks, including Gothic Stories, Monlccitte Abbey, Canterbury Tales, and The Midnight Monitor. The Mystery of the Black Convent is found in the second half of the volume and appears right after Canterbury Tales and before The Midnight Monitor. Despite the compilation’s diverse content, the white space and wide margins remain consistent across the chapbooks, providing a unified reading experience. However, the font sizes and line spacing vary from one chapbook to another, indicating differing printing practices behind each publication. Moreover, these chapbooks vary in paper quality and typography, reflecting different sources and production times. The diversity in paper of those chapbooks, from soft, white cotton to thinner, more fragile sheets, highlights the technological and material variations prevalent in the period.

Several unique features and anomalies within the compilation merit attention. For example, a chapbook with unevenly cut pages indicates a manual error during assembly and cutting, pointing to the hands-on nature of book production at the time. A notable misprint in Cecilia oe, The Victim of Treachery instead of Cecilia or, The Victim of Treachery underscores the fallibility of early printing processes. And the title page of The Mystery of the Black Convent is ripped, serving as a reminder of the paper’s fragility.

Throughout, the compilation’s pages show signs of physical wear, including ripped corners and a hole punctured through one page, suggesting a history of frequent use. These imperfections, coupled with the variation in paper aging and condition, offer a tangible connection to the compilation’s past readers and their interactions with the text.

A handwritten catalog on the front blank page lists stories beyond those printed in the chapbooks, indicating a personalized approach to collecting and cataloging by a previous owner. This feature not only adds to the compilation’s uniqueness but also suggests it served as a tailored literary collection, possibly reflecting the individual’s interests or aspirations.

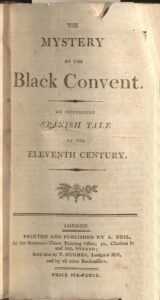

The Mystery of the Black Convent has a total of 36 pages. On its front page, the book title, The Mystery of the Black Convent, is printed in bolded font and underneath is the subtitle—AN INTERESTING SPANISH TALE OF ELEVENTH CENTURY—all in capital letters. There is a little image below the titles that looks like a mini upside-down flower bed with a few stalks of wheat on the left, a sunflower in the middle, and a rose on the right. After the image is information about the printer and the publisher of the book and the office location, along with information about the book seller and the book price.

On the very first page of text, the book title also shows up in bolded fond. There is a long line above the title and there is a short line between the title and the text. Page numbers appear in the middle of the header on each page between parentheses and the first page number marked starts with page 6. On the final page after the last paragraph, the word “FINIS” is printed in all capitals, followed by a dark horizontal line. Underneath the line there is a claim regarding the publisher and printer, A. Neil, which appears in different font sizes.

Textual History

The Mystery of the Black Convent has no known author but was printed and published by A. Neil in London. Franz J. Potter says of Neil: “Between 1814 and 1820 he published at least ten chapbooks including The Mystery of the Black Convent”(41). At least five universities own physical copies of The Mystery of the Black Convent: University of Virginia, Indiana University, Duke University, and University of Toronto. These library catalogs offer slight discrepancies in book length (varying among 17cm, 18.5cm, and 19cm) and various publication dates (with two of copies listed as published in the 1800s and two listed as published in 1806). There is a digital copy of The Mystery of the Black Convent available via Marquette University’s Gothic Archive, which lists the publication date as 1805, and where, as of 2024, the text has been downloaded 590 times.

There were no subsequent editions of The Mystery of the Black Convent published. It was originally written in English, and was never translated into any other languages. There is no preface or introduction to the chapbook, and this appears consistent with the other editions of the novel, all of which were published at the same time.

The text also does not appear to have been advertised, and does not appear to have been reprinted following its original publication. This text has not been adapted, seemingly, in any fashion. There is a clear similarity between this text and other gothic novels and chapbooks of the time period; however, it does not appear to have specifically influenced any pieces of literature following its publication. It simply appears to be one of many similar gothic texts published during this time period, which were overshadowed by each other and by even more popular works in the genre.

One of the few twenty-first century reviews of the text is negative: Douglass H. Thomson, Jack G. Voller, and Frederick S. Frank state in their Gothic Writers: A Critical and Bibliographical Guide that “The Mystery of the Black Convent plagiarized composite of salacious scenes from The Monk” (137).

Narrative Point of View

The Mystery of Black Convent is narrated from a third-person perspective by an unseen and anonymous narrator who stays out of the story. The story begins slowly and while the narration does not use complicated language, it does contain some archaic word and phrases. Despite this, the main narration reads quite smoothly and feels relatively modern. The dialogue between characters is more formal and distinctly historical. This mix gives the book a unique flavor, blending familiar storytelling with the distinct charm of its time.

Sample Passage:

“Oh, father, urge this theme no longer,” said St. Alme; “this advice partakes rather of austerity than kindness, and wears more the shape of reproof than consolation. Whatever is the cause which robs me of repose, be assured I never will reveal it: solitude and silence only can allay my pangs, death alone can terminate them.”¾”This obstinate adherence to your follies,” said the Abbots, “reminds me of the conduct of the Carthusian who was this morning interred in the Abbey cemetery. During the first year of his residence in the monastery, he was ever brooding over some secret sorrow, and indulging a train of melancholy reflections: he would, like yourself, resift the consolations of friendship, and spurn the advice of experience; but he lived to repent of his contumacy; for, at a period when he discovered that the effect of time had obliterated the impression of his woes, and the complacency of his mind had of health to enjoy it. (Mystery of the Black Convent 5)

In The Mystery of Black Convent, the third-person narration contrasts sharply with moments of dramatic dialogue. This blend serves not just to tell a story, but to juxtapose the historical depth of language with a modern storytelling approach, enriching the reader’s engagement. The archaic dialogue, set against a more accessible narrative backdrop, highlights the story’s thematic concerns such as human emotions and ethical dilemmas. This narrative choice effectively brings the historical setting to life, making it relatable to contemporary readers without sacrificing the story’s period authenticity. By doing so, the novel not only bridges the gap between past and present but also emphasizes the power of language and storytelling to transcend time. This technique, therefore, is not just a stylistic choice but a deliberate strategy to enhance the story’s resonance, showing that the essences of human experience—including deep emotions and ethical dilemmas—remain constant despite the evolving language of narration.

Summary

In the year 1140, amidst the rugged landscapes of the Spanish city of Castile, St. Alme embarks on a journey of spiritual dedication by entering the monastery of the Carthusians, a place enveloped in an aura of divine serenity and known to the locals as St. Lawrence or the Black Convent. This monastery, cloaked in its distinctive dark walls that seemed to whisper tales of devotion and sacrifice to all who approached, stands as a beacon of spiritual solace and discipline.

St. Alme, whose entry into this monastic life marked the beginning of a profound spiritual quest, was soon recognized for embodying three outstanding examples in virtue and holiness. His fervent prayer, unwavering commitment to the ascetic life, and compassionate interactions with his fellow monks distinguished him as a model of monastic piety. It was not long before his reputation for these virtues reached the ears of Father Fernando, the abbot of the monastery. Known for his wise and discerning leadership, Fr. Fernando always has a keen eye for the spiritual well-being of his flock.

However, it is during this period of seemingly unwavering devotion that Fr. Fernando begins to notice a significant and troubling change in the behavior of St. Alme. Once a beacon of joy and serenity within the monastic community, St. Alme has become withdrawn, his once bright eyes now often cast downward, shrouded in a veil of melancholy. This transformation is not only puzzling but deeply concerning to Fr. Fernando, who understands the importance of mental and spiritual health in the path to holiness.

Despite his attempts to understand the root of St. Alme’s distress, Fr. Fernando finds himself at an impasse. St. Alme, perhaps out of humility or deep inner turmoil, could not or would not provide a satisfactory explanation for his sudden shift in disposition. Concerning St. Alme’s spiritual and emotional well-being, Fr. Fernando decides to take action. He employs Fr. Martinez, a fellow monk known for his wisdom, empathy, and skill in spiritual counseling, to look into the matter more closely.

Fr. Martinez, who had spent years cultivating a deep understanding of the human soul’s complexities, approaches this task with a mixture of concern and determination. Aware of the delicate nature of his mission, he prepares himself to engage St. Alme with compassion, hoping to uncover the source of his troubles and guide him back to the light of spiritual peace and joy. The monastery, a place of profound faith and introspection, thus becomes the setting for a journey into the depths of a soul struggling to find its way back to serenity and purpose.

After several days of discrete observation, Fr. Martinez makes a startling discovery that upends the quiet monastic life of the Carthusian monastery. The enigmatic St. Alme is, in fact, not a monk at all, but a woman ingeniously disguised among the brethren. This revelation alone is enough to cause a stir, but what follows only adds layers of complexity and intrigue to the unfolding drama.

One eerie night, under the cloak of darkness, Martinez observes the figure of Alme visiting the sepulcher in the monastery’s churchyard, a place of rest for the departed souls of the monastic community. Compelled by a mixture of curiosity and concern, Martinez follows her, only to witness a scene that seems to be ripped from the pages of a gothic novel. Alme, upon encountering a moving human form within the sepulcher, lets out a shriek and faints, overwhelmed by fear and shock.

Acting swiftly, Martinez secures the sepulcher, trapping both the disguised woman and the mysterious figure within. The monastery is quickly roused, and the monks, led by Martinez, apprehend the woman and the ghostly figure, who is revealed to be none other than Anselm, an old friar long thought to have left the earthly realm.

The light of the next day brings with it a confession that will forever change the fabric of the monastic community. The woman, known to them as St. Alme, reveals her true identity to Fr. Fernando as Beatrice, the daughter of Anselm, who is in reality Raymond de Spalanza, a nobleman. Her story unfolds, revealing a tapestry of love, duty, and desperation. Beatrice explains that she had been compelled to assume a disguise and enter the monastery to find her ailing father, who had sought the monastery’s solace for a peaceful demise away from the world’s eyes.

In a twist of fate, Beatrice’s lover, Alphonso, driven by undying love and determination, arrives at the monastery in search of her. Their love had been thwarted not by lack of affection but by cruel circumstances, as Alphonso had been unjustly imprisoned due to the machinations of his own father.

The revelations bring a sense of clarity and compassion to the hearts of all involved. Fr. Fernando, moved by Beatrice’s plight and the genuine love between her and Alphonso, seeks the approval of Raymond de Spalanza. With the nobleman’s blessing, Fernando performs a ceremony of profound significance in the chapel of the Black Convent, uniting Beatrice and Alphonso in holy matrimony.

Bibliography

The Mystery of the Black Covenant. An Interesting Spanish Tale of the Eleventh Century. London: A. Neil.

Potter, Franz J. Gothic Chapbooks, Bluebooks and Shilling Shockers: 1797–1830. University of Wales Press, 2021.

Thomson, Douglass H., Jack G. Voller, and Frederick S. Frank, editors. Gothic Writers: A Critical and Bibliographical Guide. Greenwood Press, 2002.

Researcher: Rui Chen

How to cite this page: MLA: “The Mystery of the Black Convent.” Project Gothic, University of Virginia, 2024, https://gothic.lib.virginia.edu/access-the-archive-2/the-mystery-of-the-black-convent/